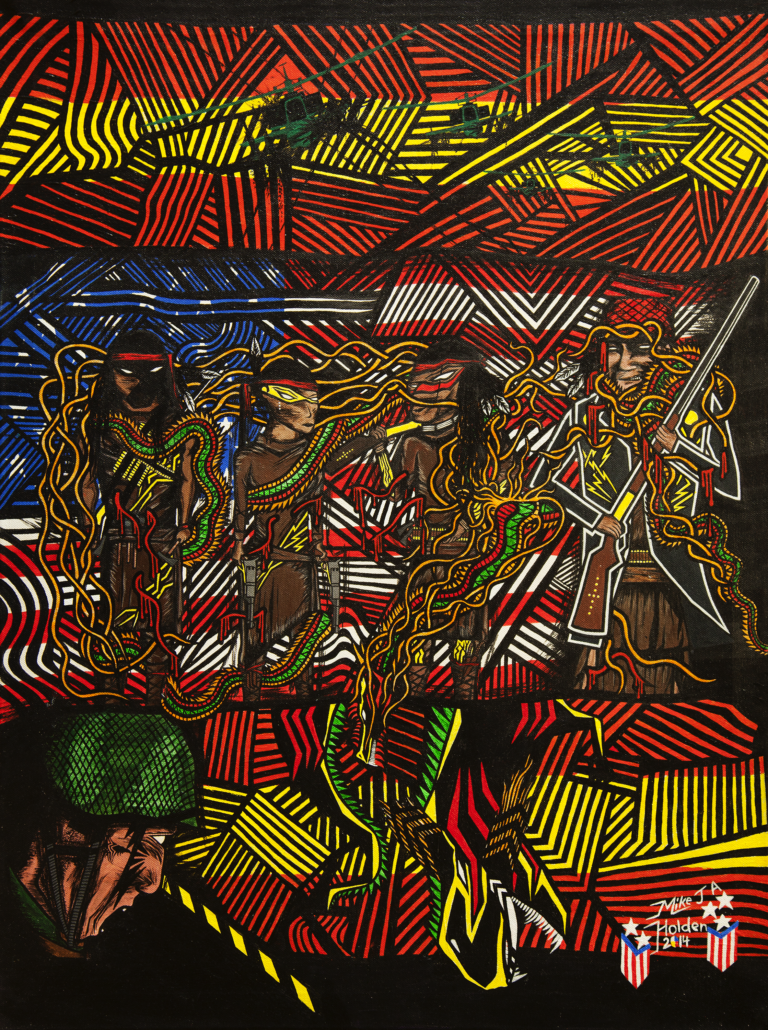

Geronimo

23″ x 31″ Acrylic on Canvas

Apache warriors are honored for the courage of their nations which fought with unparalleled bravery against the United States between 1849 and 1886, when Geronimo surrendered, and to a lesser extent for another 38 years after. The tendrils of lightning encasing the warriors are a depiction of how the first peoples saw the lethal power of gunfire that struck men dead with a thunderous flash. The serpent with the many tentacles strangling Geronimo and piercing through the skin of the Apache warriors depicts the mass genocide inflicted by the US.

The Apache helicopter, the most lethal helicopter in the world, was named after the Apache Warriors for their ferocity in battle. Some of the weapons used by the Apache warriors have been adopted by the US military such as the Tomahawk and several combat knives. And as early as 1940, American paratroopers of all ancestries adopted “Geronimo” as a battle cry for jumping into combat.

Today the Apache warrior tradition continues as a proud and disproportionate number of patriotic Apache men and women who serve in the American military. For this reason the red, white, and blue of the American flag appears in the background—a flag countless Apache veterans have heroically fought under for nearly a century.